20 QUALITY | October 2013 www.qualitymag.com

In 2011, Sipho Tjabadi, general manager, Eskom

Quality Management, South Africa, spoke at the

ASQ Audit Division Conference. To punctuate his

keynote address, Tjabadi brought a video titled,

“The Cost of Quality.” For seven minutes the audience

was transfixed while several quality failures

were presented, root causes offered, and total cost

in materials (and, too often, life) were calculated on

screen. After the conference the video was posted to

the Audit Division website, where it continues to be a

popular page.

The video powerfully illustrates cost of quality. But

what does cost of quality really mean? To answer the

question, let’s take a step back. Define quality. Take a

moment to ponder.

A visit to Dictionary.com will bring us to the

following list:

qual·i·ty (kwoliti)

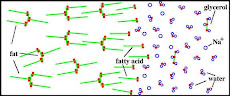

1. an essential or distinctive characteristic, property,

or attribute: the chemical qualities of alcohol.

2. character or nature, as belonging to or distinguishing

a thing: the quality of a sound.

3. character with respect to fineness, or grade of excellence:

food of poor quality; silks of fine quality.

4. high grade; superiority; excellence: wood grain

of quality.

5. a personality or character trait: kindness is one of

her many good qualities.

Character. Nature. Excellence. Did any of these

terms appear in your definition of quality? While

most of us can identify what a quality product or

service is, it is often more difficult to convey that

to someone else. How many times have you—as a

quality professional—when a person asks you what

quality is, allowed the asker to supply the answer

and then filled in the gaps? That’s fairly common

with ASQ members. In fact, in recent informal polls

on ASQ social media, when asked “what is quality?”

a number of visitors answered “whatever the customer

says it is.”

The customer will generally relate quality to the

way in which a product works. While a good starting

point, quality is not only what a product is but

also what a methodology or tool does. This is certainly

the way a quality professional must think.

Stating what quality “does for me” is not only a

way of explaining to family, neighbors and coworkers

but a means of justifying its importance to

senior management.

So, where are we in our quest to define quality?

Quality is:

• Waste reduction

• Continuous improvement (which might include

process improvement)

• Performance excellence (there’s that word excellence)

• Product safety

• Service delivery

• Exceeding customer expectations

Depending on what you are trying to do, quality will

mean something different to you.

With quality more or less defined, we can finally

turn to cost of quality. With the multiple quality definitions

in circulation, it is no wonder cost of quality

is defined in different ways. Unlike the definition of

quality, however, many of the terms used to define

cost of quality are incorrect.

WHAT IS COST OF QUALITY?

Cost of quality is often thought of as the price of

creating a quality product. While on the surface

this appears to make sense, this definition is absolutely

incorrect.

In actuality, the cost of quality is the cost of NOT

creating a quality product or service. What is the

difference? The former (incorrect) definition covers

product/service costs only. Cost of quality covers any

cost that would not have been expended if quality

were perfect.

In 1999, ASQ Quality Costs Committee

published the third edition of “Principles of Quality

Costs: Principles, Implementation, and Use” (ed.

Jack Campanella, ASQ Quality Press), beginning

the book with references to costs associated

with quality.

• Prevention Costs—The costs of activities specifically

designed to prevent poor quality in products

or services.

• Appraisal Costs—The costs associated with measuring,

evaluating, or auditing products or services to

ensure conformance to quality standards and performance

requirements.

• Failure Costs—The costs resulting from products or

services not conforming to requirements or customer/

user needs. Failure costs are divided into internal

and external failure categories.

WHAT DOES

(COST OF) QUALITY MEAN?

MANY OF THE TERMS USED TO DEFINE COST OF QUALITY ARE INCORRECT.

SPEAKING OF QUALITY

020-QM1013-CLMN-ASQ.indd 20 9/17/13 3:33 PM

www.qualitymag.com October 2013 | QUALITY 21

Moving Quality to the Point of Production

The 4.5.4 SF excels in the harsh environment of machine shops and manufacturing cells.

Place it where accurate dimensional inspection is needed.

Learn more about the effect of thermal conditions on measurement accuracy at

www.HexMet.us/qm1013 or call 800.274.9433 to see all the 4.5.4 SF has to offer.

We are Hexagon Metrology.

WE ARE

SHOP FLOOR

To view a demo of the 4.5.4 SF, scan this

code or visit www.HexMet.us/qm1013a.

• Internal Failure Costs—Failure costs occurring prior to

delivery or shipment of the product, or the furnishing of a

service, to the customer.

• External Failure Costs—Failure costs occurring after delivery

or shipment of the product —and during or after furnishing

of a service—to the customer.

• Total Quality Costs—The sum of the above costs. This

represents the difference between the actual cost of a

product or service and what the reduced cost would be if

there were no possibility of substandard service, failure

of products, or defects in their manufacture.

Yes, this is a daunting list of costs. But quality is essential.

There is a cost to attaining and improving quality, but there

is a bigger cost in failing to produce quality work. Don’t allow

a definition to get in the way of your work. You know what

quality is. Achieve it!

You can fi nd more about cost of quality, including free articles and case

studies, at http://asq.org/cost-of-quality/index.html.

020-QM1013-CLMN-ASQ.indd 21 9/17/13 3:33 PM

Copyright of Quality is the property of BNP Media and its content may not be copied or

emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario