I

and Their Impact on Cooling Towers

BY SIMONA VASILESCU

n 2017, a runner dressed as a camel completed the London lvfarathon.Run11ing 26.2 miles is a huge achievement in and of itself; doing it while wearing a highly insulating costume

makes it much more difficult. The costume trapped warmth,

making it harder for the runner to cool down. This same prin ciple applies to water cooling systems coated in biofilm. The good news is that maintenance managers in charge of these systems have the power to take control of the situation.

There are three stages ofbiofilm development:

1. Attachment: A biofilm starts when a few pioneer bacteria use specialized chemical hooks to adhere to a surface. This can occur in response to many factors, ranging from attachment sites present on the pipe surface, nutritional cues or sub inhibitory concentrations of stress factors such as biocides. It is thought that the first colonists of a biofilm adhere to the surface initially through weak Vander Waals forces and hydrophobic effects. Interestingly, the number of planktonic bacteria in the water does not correlate with either the for-

What are biofilms?

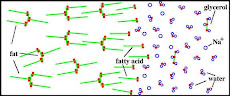

Many different types of planktonic (free-floating) bacteria can be found dispersed throughout water in a water cooling system. These come together to form a sessile aggregate, which adheres to the inside of the system's pipes. These attached bacteria then produce a matrix of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), often referred to as slime, covering them completely.

This matrix is a collection of DNA, proteins and polysac

charides that form a protective housing around bacteria, cre ating a safe space and preventing biocide treatment from reaching the bacteria. In fact, bacteria in a biofilm are 10 to

1,000 times more resistant to treatment than in their plank

tonic, free-floating form.1

16 INDUSTRIAL WATERWORLD NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2017

3. Dispersal: Dispersal of bacteria from the biofilm colony is an essential stage of the biofilm life cycle, enabling its spread to other parts of a water cooling system. This happens when bacteria within the biofilm spontaneously secrete enzymes, such as dispersin B and deoxyribonuclease, to break out of the slime matrix and back into the water.

This reverts some of the bacteria back to their free-floating planktonic state and thus free to start a new colony ofbiofilm elsewhere in the system. Researchers have tried to harness

Resilience

Once a biofilm has advanced, it forms a complex structure in which different bacteria occupy different environments. This sophisticated approach means bac

teria towards the outside of the commu

nity have a very different structure from those deep within the matrix. It is this diversity that adds to the stubbornness, as treatment will need to target many different physiologies.

bacterial strain while the other strains may remain unaffected. Without breaking down thiS complete protective layer, the bacteria will remain protected and free to multiply. Furthermore, the bacteria con tained within the matrix use quorum sensing, meaning they are constantly un dergoing genetic divergence. This gives biofilms phenomenal recovery and re growth abilities after a population hit, often caused by treatment attempts.

from the hot item to the cool water becomes much more difficult. It could be compared to someone trying to cool down but re fusing to remove their coat: it's inefficient. A biofilm layer of just 0.1 mm can reduce efficiency so much that the associated electricity costs to power your plant can increase by a factor of four compared to a system containing the same thickness of

Health Hazards ·

The United States National Institutes of Health says that 80 percent of chronic infections are biofilm-related. This re search looked specifically at biofilms in side the body, but biofilms can also occur in many other places, including industrial cooling towers. They are associated with the spread of Legionella bacteria, which can cause Pontiac disease, or worse, Le gionnaire's disease, a potentially deadly form of pneumonia.

bae. These single-celled organisms join the biofilm colony and feed on the bacteria within it, including Legionella bacteria. The ingested Legionella then proliferate within the amoeba as it provides suitable conditions for the Legionella to multiply. This makes them a significant health haz ard in many industries and is why it is so important to manage and control the pres ence ofbiofilms.

Costly Coats

Many industries with processes that de pend on heat being quickly removed from a production area rely on water cooling systems. If the water cooling system pipe is coated in biofilm, then the heat exchange

calcium carbonate scale.

Biofilms often aren't considered as the cause of increased electrical costs, perhaps because they are rarely detected. Bioftlms are generally just a few microns thick, 100 times smaller than the cross section of a strand of hair, and plant managers are not actively looking for them. A water treatment specialist, however, can inspect cooling systems using the latest techniques and analyze samples to detect the presence of biofilms and advise on appropriate treatment.

Biofilms are also a leading cause of microbiological corrosion.

Biofilms can contain sulfite-reducing or iron-depositing bacteria that destroy steel, wreaking havoc on water cooling system pipes. This microbiological corro

sion is 1 0 to 1,000 times quicker to de

velop and 10 to 100 times more aggres

sive than standard corrosion.

They can contain sulfite-reducing or iron-depositing bacteria that destroy steel, wreaking havoc on water cooling system pipes. Microbiological corrosion accounts for up to 50 percent of the total costs of corrosion to economy. Compared with standard corrosion, it is 10 to 1,000 times quicker to develop and is 10 to

100 times more aggressive. Ifleft untreated, this cari have costly

18 INDUSTRIAL WATERWORLD NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2017

consequences to mission-critical equipment in cooling systems

-leading to expensive repair work and downtime.

Breaking Down the Protective Layer

A treatment that breaks down the complex biofilm mech anism, exposing the bacteria hiding within, is critical. NCH Europe's Water Treatment Innovation Platform has developed a patented liquid-based treatment called BioeXile that has been designed to keep up with the diverse and resilient matrix of biofilms and to destroy it. The exposed bacteria can then be treated with biocide, preventing them from going on to recolonize.

Unlike completing the London Marathon in a camel costume, there's no sense of accomplishment for a cooling tower working extra hard. By treating biofilms, you are removing an unnec essary and costly insulating layer, allowing the cooling tower to work more efficiently, reducing the risks associated with Legionella, and addressing the problems of microbiological corrosion outlined above. liMN

References

1.Monroe, D. "Looking for Chinks in the Armor of Bacterial Biofilms," PLoS Biology,

5(11): e307, November 2007.

Circle No. 151 on Reader Service Card

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario