What Is C. diff?

In 2009, officials at Jewish Hospital-Mercy Health knew they had a problem — its Clostridium difficile (C. diff) incidence rate had hit an all-time high of 25.27 per 10,000 patients and they didn’t know why.

“We had to do something,” says Jenny Martin, manager of quality administration.

The Cincinnati hospital convened a task force of clinical services professionals, physicians, nurses, administrators and environmental service workers to assess the spike in infections caused by this deadly bacterium, which ravages the intestines. They found that the patient makeup of the 209-bed hospital was partly to blame. C. diff is a bacterium that preys on the sick, particularly those who are elderly or immunocompromised — both of which Jewish Hospital-Mercy Health had plenty of.

“We have an older patient population — the average patient age is 72 years old — and we have a blood and bone marrow transplant center,” Martin says. “The type of antibiotics we use makes these patient populations very susceptible to C. diff infections.”

Hospital officials acted quickly and were able to slash the facility’s high C. diff rate by 50 percent in six months by standardizing care, adopting stricter antibiotic controls and incorporating new room-cleaning protocols.

“But in all honesty, the changes to our environmental cleaning practices had the most significant impact out of all of the changes we made,” says Martin.

As this example shows, when it comes to hospital-acquired infections custodial cleaning practices can make a world of difference.

About 50 percent of the population naturally carries clostridium difficile (C. diff) in their intestines, states Benjamin Tanner, president of Antimicrobial Test Laboratories, Round Rock, Texas.

“It lives in harmony with the other bacteria in your intestines and doesn’t cause problems,” he says. “The only time it makes individual’s ill is when people go on multiple or individual antibiotic therapy.”

The bacteria, C. diff, exists within the body in a vegetative state and doesn’t make people sick, unless illness, disease and antibiotic use puts them at risk, Tanner explains. At that point, C. diff mutates into its active state, forming a resistant end spore that becomes difficult, if not impossible, to eradicate from the environment.

“These spores are exceedingly difficult and challenging to disinfect,” says Tanner. “Once they enter the environment, there are only a few disinfectants and technology that can kill it. The spores tend to get everywhere. They move easily from surface to surface.”

While antibiotics cannot always treat these infections, good cleaning and hygiene can prevent them from spreading. It’s safe to say when it comes to C. diff the best offense is a good defense.

Cleaning with bleach is the No. 1 means of attacking C. diff spores, say experts.

“There are probably only four to five EPA-registered bleach-based disinfectants with a C. diff claim. These have passed laboratory testing showing they can kill millions of C. diff spores on a surface,” says Tanner. “They are currently the best way to clean C. diff from a surface.”

Darrel Hicks, director of environmental services and patient transportation at St. Luke’s Hospital in St. Louis, and author of “Infection Control For Dummies,” agrees that the best disinfectants used in a C. diff situation are bleach based.

“The spore is very difficult to break through and conventional disinfectants won’t do it. You have to use a sporicidal disinfectant,” he says. “Though bleach can be highly corrosive to surfaces, it is effective against C. diff and our goal is to help save people’s lives.”

As an alternative to bleach, some facilities are experiencing success in the fight against C. diff by using accelerated hydrogen peroxide (AHP) products. These are clear, colorless and odorless products that are less harsh than bleach counterparts.

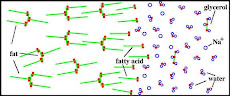

Composed of hydrogen peroxide, surface acting agents (surfactants), wetting agents (allows liquid to spread easier) and chelating agents (helps to reduce metal content and/or hardness of water), AHPs have proved successful in killing C. diff spores. In fact, according to testing done by “American Journal of Infection Control,” when used as directed, AHP proves to be as effective as bleach.

No matter which disinfectant is used against C. diff, Tanner advises paying critical attention to dwell times in patient rooms.

“There’s a linear relationship between how long a disinfectant remains wet on a surface and how much disinfection you get,” he says. “You can take a great disinfectant, such as bleach, and if you only leave it on a surface for five seconds, you won’t get nearly the effect you need. Contact time is critical for a liquid disinfectant. If you don’t use it long enough, you won’t get the same level of disinfection.”

At St. Luke’s Hospital, Hick’s staff cleans C. diff patient rooms twice daily. Housekeepers perform thorough cleaning once a day, and then come back a second time to cleanse all high-touch surfaces in the room.

“We go over these surfaces with bleach wipes,” Hicks says. “We go after the spores on a daily basis rather than just on discharge like a lot of hospitals do.”

Taken from CleanLink ,April 2013

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario