Does Chlorine

Get a Bad Rap?

When it comes to disinfection at treatment plants, chlorine has quite the reputation. To some, it’s

known as a reliable and trusted solution. To many others, especially among the public at large,

it’s looked at with skepticism and concern – but that may be simply a matter of not knowing the

facts. Either way, it’s one of the ubiquitous aspects of water and wastewater disinfection… and for

good reason.

To separate fact from fiction and clear up exactly how chlorine should be utilized at treatment

plants, we spoke with Evoqua Water Technologies’ Daryl Weatherup, director of marketing for the

company’s Wallace & Tiernan brand. He walked us through the different forms chlorine can take, its

reputation among the industry and ratepayers, and how to determine its best use at a given plant.

How is chlorine utilized at treatment plants?

Chlorine is used in many water and wastewater applications, not only in the U.S. but around the

world. It really has been the most predominant method of disinfection for the past century.

What’s different about chlorination, though, is that it’s not just available in one format. There

are several formats that it is available in: gaseous chlorine, liquid sodium hypochlorite (bleach

being the common household name), dry or solid form tablets or pellets of calcium hypochlorite, and

then the fourth main way to apply chlorine in water and wastewater systems is actually generated

onsite through the electrochlorination of brine or saltwater solutions.

Do you think that chlorine has the reputation that it deserves?

I think there are two sides to the reputation of chlorine and chlorination. On the one hand,

chlorine has a great reputation as being a widely used disinfectant that has really transformed

the water industry and improved human health, environmental water quality, and sanitation over the

last 100 years.

But there’s also a negative side to it. When chlorine’s applied in the right amount to the

controlled process, it is a good

disinfectant. But if it is released in a spill or leak in higher doses, it can be harmful. I think

that is where some of the negative connotation comes about and the reputation it has as being

potentially unsafe.

Do you think that reputation it has as a dangerous chemical is more prevalent among ratepayers or

with the professionals who are actually disinfecting water?

Water Online • www.wateronline.com

1

&A

I think it’s a little bit of both. At the consumer ratepayer level, they get a lot of their

information through the media, and the media doesn’t always report safety incidents in the right

way. Oftentimes there are accidents that happen that are not caused by chlorine but get reported as

involving chlorine. At least in the U.S., there are a higher number of safety incidents with other

liquid chemicals and other dangerous substances in treatment plants than there are with chlorine

gas.

On the professional level, there is competition with other methods of disinfection. Some

are chemical-free but provide no residual disinfectant, which is required in municipal water

distribution. Those that offer chemical-free solutions might add to the negative reputation that

chlorine can have.

What advances in process and technology are making chlorine safer today?

There are quite a few things that have changed over the last 100 years with the way chlorination is

done today. It started out in

1913 with the first commercial chlorinator, and the technology has improved quite a bit since.

The main things that have changed are the engineering methods available, the materials of

construction available — metal alloys, engineered plastics, and so forth — that have really

allowed us to improve the quality of the actual chlorine dosing systems themselves, the

chlorinators. We’ve engineered chlorinators to be more durable, have fewer moving parts, and be

inherently safe.

Aside from that, there are additional devices that help make the overall chlorination systems

safer, such as double- check valves and seals, safety shut-off valves, or emergency vapor

scrubbers — also manufactured by Evoqua — which can scrub all of the chlorine gas out of a room

even in the event of a full-scale release. We’ve manufactured this for our systems as a secondary

safety system. There are other ancillary items, like gas detection systems and fire safety doors,

that can go towards making the overall system very, very safe.

What alternatives to chlorination are out there?

There are no other alternative methods that provide the same cost-effective benefits as

chlorination or are as widely used

as chlorination. There are other methods that are called “alternate disinfectants,,,”

including UV and ozone, as well as various other types of disinfectants that are innovative but not

as widely used.

How should a treatment plant assess the different forms of chlorine that exist and make a selection

on which one is the best for them?

This is probably the question I receive the most. The best answer that I can give is that it’s

really a local decision that needs to take

into account several factors. It is not just about capital costs or operating costs alone.

We work with the water utility and ask them what their decision-making factors and drivers

are. Are there any environmental concerns? Is the facility in a rural area or an urban area? What’s

the distance away from the nearest chemical supplier?

Beyond that, we look at their water-quality

goals and disinfection targets, along with the capacity and treated flow rate. That will determine

what the total chlorine demand is. We also take into consideration, from that, how often they might

need to order chemicals.

As a manufacturer of all four types of chlorination systems, not to mention UV, we offer expertise

on which format of

chlorine is best for the given application. I think it’s important to have a well-balanced view of

what is available and not be pushed towards one method or another. Additionally, there are

consultants we work with who also specialize in this selection process. The U.S. EPA and AWWA

both offer information about selecting disinfectants and have published resource manuals on

those as well.

If someone tells you they believe using chlorine as a disinfectant is dangerous, how do you

respond?

Anything can be dangerous when it’s mishandled, and that chlorine is by far the safest, most

widely used, and most reliable form of disinfection. One of the things that works against switching

away from chlorination to other methods is typically the cost, the reliability, and the

availability to the general public. That’s why, after a century, it’s still the most widely used

form of disinfection in the world today.

Water Online • www.wateronline.com

2

martes, 15 de noviembre de 2016

The best Scientist

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

Vistas de página en total

GREEN CHEMICALS

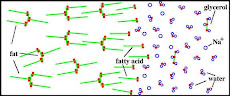

The Green Seal certification is granted by the organization with that name and has a great number of members contributing with the requirements to pass a raw material or a chemical product as "green". Generally for a material to be green, has to comply with a series of characteristics like: near neutral pH, low volatility, non combustible, non toxic to aquatic life, be biodegradable as measured by oxygen demand in accordance with the OECD definition.

Also the materials have to meet with toxicity and health requirements regarding inhalation, dermal and eye contact. There is also a specific list of materials that are prohibited or restricted from formulations, like ozone-depleting compounds and alkylphenol ethoxylates amongst others. Please go to http://www.greenseal.com/ for complete information on their requirements.

For information on current issues regarding green chemicals, see the blog from the Journalist Doris De Guzman, in the ICIS at: http://www.icis.com/blogs/green-chemicals/.

Certification is an important — and confusing — aspect of green cleaning. Third-party certification is available for products that meet standards set by Green Seal, EcoLogo, Energy Star, the Carpet & Rug Institute and others.

Manufacturers can also hire independent labs to determine whether a product is environmentally preferable and then place the manufacturer’s own eco-logo on the product; this is called self-certification. Finally, some manufacturers label a product with words like “sustainable,” “green,” or “earth friendly” without any third-party verification.

“The fact that there is not a single authoritative standard to go by adds to the confusion,” says Steven L. Mack M.Ed., director of buildings and grounds service for Ohio University, Athens, Ohio.

In www.happi.com of June 2008 edition, there is a report of Natural formulating markets that also emphasises the fact that registration of "green formulas" is very confused at present, due to lack of direction and unification of criteria and that some governmental instittion (in my opinion the EPA) should take part in this very important issue.

Also the materials have to meet with toxicity and health requirements regarding inhalation, dermal and eye contact. There is also a specific list of materials that are prohibited or restricted from formulations, like ozone-depleting compounds and alkylphenol ethoxylates amongst others. Please go to http://www.greenseal.com/ for complete information on their requirements.

For information on current issues regarding green chemicals, see the blog from the Journalist Doris De Guzman, in the ICIS at: http://www.icis.com/blogs/green-chemicals/.

Certification is an important — and confusing — aspect of green cleaning. Third-party certification is available for products that meet standards set by Green Seal, EcoLogo, Energy Star, the Carpet & Rug Institute and others.

Manufacturers can also hire independent labs to determine whether a product is environmentally preferable and then place the manufacturer’s own eco-logo on the product; this is called self-certification. Finally, some manufacturers label a product with words like “sustainable,” “green,” or “earth friendly” without any third-party verification.

“The fact that there is not a single authoritative standard to go by adds to the confusion,” says Steven L. Mack M.Ed., director of buildings and grounds service for Ohio University, Athens, Ohio.

In www.happi.com of June 2008 edition, there is a report of Natural formulating markets that also emphasises the fact that registration of "green formulas" is very confused at present, due to lack of direction and unification of criteria and that some governmental instittion (in my opinion the EPA) should take part in this very important issue.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario