Controlling Odors

Using Enzyme Cleaners

By Kassandra Kania

Foul-smelling restrooms are a frequent source of complaints

from building occupants — and a challenge for custodians charged with

controlling odors and keeping restrooms clean and fragrant. Continual use makes

controlling odors difficult, and masking malodors often intensifies the

problem. To rid restrooms of offensive smells, custodial departments need to

eliminate the cause of the odor — namely uric acid — and this is where

traditional cleaners often fall short, say distributors, who instead stress the

use of enzyme cleaners when controlling odors.

“Typically, in restrooms, the biggest issue is the smell of

urine,” says Jim Flieler, vice president of sales at Swish Maintenance Ltd. in

Peterborough, Ontario, Canada. “Often, urine splashes to floors and gets into

the grout, causing a uric acid odor that’s offensive. Once it embeds itself in

grout, traditional cleaners cannot get rid of that smell, and it doesn’t help

that most restrooms have poor air filtration.”

While the majority of custodial departments still favor

all-purpose cleaners for restrooms, some are beginning to introduce

enzyme-based cleaners into their cleaning regimens to remove or control odor

causing bacteria, particularly in hard-to-reach porous surfaces.

Anthony Crisafulli, owner of Atra Janitorial Supply in

Pompton Plains, N.J., has had tremendous success selling enzyme cleaners,

specifically in K-12 school districts.

“In any facility, not just schools, the chief complaint is

the odor coming out of the bathrooms,” he says. “If you can control odors,

people aren’t going to complain as much if the bathroom’s a bit dirty. It’s the

odors that kick up those complaints so quickly.”

An Introduction to

Enzyme Cleaners

To understand how enzyme cleaners — also known as

bio-enzymatic cleaners — can be advantageous in restroom cleaning, custodial

managers need to first understand what they are and how they work.

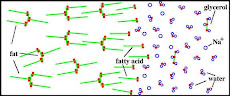

In essence, enzymes are chemicals made by bacteria to digest

waste. Enzyme-based cleaners contain enzyme systems that break up waste

molecules, which are then digested by the bacteria and converted into carbon

dioxide and water. The waste that generates foul odors in the restroom serves

as food for the microorganisms.

According to Eric Cadell, vice president of operations for

Dutch Hollow Supplies, Belleville, Ill., there are two types of enzymatic

cleaners: those that contain surfactants and those that don’t.

“In both cases, the enzymes are kept dormant until they come

into contact with the food source,” Cadell explains. “That food source is going

to be body fats, oils and uric acids. Typically the enzymes are mixed with

water, which awakens them, and they immediately start looking for that food

source. If they can’t find that food source, the enzymes will die.”

Because the enzymes remain active as long as the food source

is present, they are most often used on restroom floors, around and below

toilets and urinals, in drains and in grout lines.

“Most floors in restrooms are grouted ceramic tile,” says

Crisafulli. “Many custodians are trained to mop and clean their floors with

general purpose cleaner, but that doesn’t get into the grout lines and clean

the subsurface. We know that urine penetrates into those grout lines, and

general surface type cleaners just don’t clean that deeply.”

When choosing an enzyme-based cleaner, custodial managers

should keep in mind that not all enzymes are created equal. Manufacturers have

developed different strains to target specific types of organic waste.

“There are so many different kinds of enzymes, so managers

want to make sure that the one they purchase is designed for what the staff is

trying to clean,” cautions Cadell. “Enzymes designed for a drain line in a

kitchen, for example, go after oils and fat, so that same product won’t work in

a restroom because it doesn’t eat uric salt.”

Although enzymatic cleaners designed for restrooms are most

commonly used on floors, they can also serve as general-purpose cleaners for

high touch points, such as mirrors, faucets and door handles.

“Part of our goal is to help departments reduce the amount

of different chemicals used when cleaning restrooms,” says Crisafulli. “By

using microfiber technology and enzymatic cleaning products, the custodial

staff can clean an entire restroom with just one product — although we still

recommend disinfecting touch points.”

Performance, Green

Benefits Of Enzymatic Cleaners

Reducing the amount of chemical used in restroom cleaning

can streamline purchasing and product storage. But will managers struggle to

convince custodians to give up traditional cleaning products in favor of

enzymatic cleaners? Distributors agree that once workers understand how

enzymatic cleaners work, educating them on their performance benefits — as well

as the differences between traditional and enzymatic cleaners — may persuade

them to accept these products into their repertoire.

For example, custodial departments concerned with green

cleaning will be pleased to know that enzyme-based cleaners are safe for the

environment, as well as human health, according to distributors.

“They’re not harmful because they’re not caustic, and most

are at neutral pH levels,” notes Cadell.

In fact, in most instances, enzyme-based cleaners eliminate

the need to use harsh chemicals. Additionally, the waste consumed by the

enzymes is converted into carbon dioxide and water.

“That in itself is a green philosophy,” says Cadell. “It’s

not killing anything, and it’s not a surfactant that gets into streams or

wastewater, so it’s not causing any harm.”

One of the major differences between traditional cleaners

and enzymatic cleaners is that enzyme-based cleaners perform residual cleaning;

that is, they continue cleaning well after the product has been applied. This

improved product performance contributes to improved productivity.

“It’s cleaning after you’ve cleaned,” explains Cadell. “When

you use the enzyme cleaners, they start to travel down the p-traps and grout

lines, and after you’ve cleaned and left, they’re still working on the odor

source.”

According to Crisafulli, some enzyme-based cleaners continue

to destroy odor-causing organisms for up to 80 hours, as long as the surface

remains wet and there is a food source present.

“A lot of people say, ‘When I mop my bathroom floor it’s dry

in 15 minutes, so how does the product continue to work if the surface has to

remain wet?’” he says. “The answer is, on a porous floor, like a grouted floor,

the tile may dry but that grout line stays wet for hours, and that’s where we

want a deeper clean.”

Distributors also stress that on non-porous surfaces,

enzyme-based cleaners can penetrate into areas where traditional cleaners can’t

reach.

“Even on something as simple as traditional floor finish on

a vinyl tile floor, there are micro-abrasions and scratches due to normal foot

traffic,” says Crisafulli. “Mopping with a bio-enzymatic cleaner will allow you

to get into those hard-to-clean places and give you that deeper cleaning

ability.”

Proper Handling And

Use of Enzyme Cleaners

In order for enzyme-based cleaners to work correctly,

custodial staffs need to be trained on the proper procedures for handling and

using these products.

“Enzymes have a very short life cycle,” notes Cadell. “They

are kept dormant in a suspension agent until they are diluted with water, at

which point they need to find a food source quickly, or they will die.”

Once the enzymes are activated, they need to be applied

directly to the surface that needs cleaning.

“These are not the type of products you can toss into your

mop water,” warns Cadell. “They’ll start to attack things inside the mop,

because the first place the enzyme touches and finds its food source is the

first place it’s going to attach and eat.”

Cadell recommends spraying the enzymatic cleaner close to

the area being targeted — within a foot or less for grout lines.

If custodians are using enzymatic-based cleaners on touch

points, distributors encourage managers to train staff to target those areas

first, and then move on to urinals, toilets, and finally, floors.

“We suggest workers clean the entire restroom with the

bio-enzymatic cleaner, and then the last thing they do is mop the floors with

it,” says Crisafulli. “Workers should start with dry processes — always working

from high to low — and then work their way from the farthest point in the

restroom to the door.”

Because disinfectants will attack enzymes, distributors

advise custodians to disinfect before using enzymatic cleaners.

“Some managers train their people to go in and spray enzymes

to take care of odors and then use disinfectant on top of that,” says Cadell.

“In these cases, they’ve killed the product before it’s even had a chance to

work.”

The last area to be cleaned with the enzymatic cleaner is

the floor. In addition to training custodians on daily procedures, Crisafulli

advises them to do a restorative-type cleaning on floors every three months

using an enzymatic cleaner.

“If we have a lot of odor complaints, we’ll do an evaluation

and find that it’s usually because of the floors,” he says. “We’ll encourage

departments to do a deep cleaning or scrubbing with the enzymatic cleaner and

then do a heavy wet mop with the enzymatic cleaner for three or four days in a

row. That way we know the surface is going to stay wet for 24 to 36 hours, and

the enzymatic cleaner will continue to break down the odor-causing bacteria.”

While the industry has been slow to adopt enzymatic

cleaners, Flieler predicts that sales will pick up over the next year due to

safer blends, wider availability and more general knowledge.

“It’s common sense,” he says. “Bio-enzymatic cleaners are

safer to use, safer for the environment and safer for human health. They

continue to clean well after the initial application, and you displace those

potentially disease-causing bacteria. Once we introduce people to these

products and explain what they are and how they work, they never go back.”