Specialties spotlight

Many chemical players in mature markets see value-added products as vital to compete against low-cost commodities from Asia and the Middle East

FOR THE chemical industries of Western Europe, North America and Japan, the future seems to lie in specialties. But their transformation into sectors that are predominantly manufacturers of value-added products will probably be a slow process.

First, they have to downsize their commodity chemical businesses, which have been losing competitive advantage to producers

in the Middle East and the emerging economies, especially Asia and Latin America.

Restructuring of chemical production in favor of an expansion in specialities, in which mergers and acquisitions (M&As) will play a big role, could be particularly crucial to the prospects of the chemical industry in Western Europe.

Its commodity operations, especially in bulk polymers, are coming under intense pressure from low-cost producers in the Middle East. They appear to have no option but to move from high-volume, low-margin products to lower-volume, premium-priced chemicals.

The need for a specialties strategy is less urgent in the US, where relatively cheap natural gas is keeping down the feedstock costs of commodity producers. But even in North America, an expansion into specialties seems inevitable in the longer term.

The prospects of permanently high oil prices are a major handicap to commodity businesses without access to plentiful supplies of inexpensive feedstocks.

In addition, the increases in capacity for bulk chemicals and high oil prices are occurring at a time of uncertain recovery from an economic crisis, which is not over yet. Some multinational chemical companies are already planning for a double-dip recession.

"Previously, we've had an economic downturn with new petrochemical capacity coming on stream or a downturn with high oil prices," explains Paul Hodges, chairman of the UK-based consultancy International eChem.

"But we have not had all three - an economic crisis, high oil prices and new capacity occurring together. Restructuring will be inevitable and some of it may have to be quite radical and painful.

"Chemical companies in the developed world will have to exploit their expertise in chemistry by moving into the manufacture of more sophisticated chemicals in which they try to gain the benefits of lower operational costs. Or they will have to concentrate on being R&D [research and development]-based solution providers," Hodges believes.

Chemical companies in Europe, North America and Japan already dominate the global market for specialties. Now, with more producers in these areas wanting to become big specialty players, that supremacy will be considerably reinforced.

EXPANSION POSSIBILITIESLocal specialty producers are gathering strength in the emerging economies, particularly in China and India. But they are unlikely to be major global operators for several years.

"There are now many chemical companies and private equity funds wanting advice on how to expand into specialties," says Chris Stirling, a chemical consultant at the global consultancy KPMG , in London, the UK.

"It is the bottom of a cycle, so this is a good time to get into specialties. But large acquisitions will be difficult. Much of the activities could be in smaller takeovers with the main objectives being access to technologies and know-how," he adds.

"Restructuring will be inevitable"

Paul Hodges, chairman, International eChem German chemical major BASF's €3.8bn ($5.3bn) acquisition of Switzerland's Ciba Specialty Chemicals, completed last year, and US-based Dow Chemical's $15bn (€10.7bn) recent takeover of rival Rohm and Haas to become more of an asset-light, value-added player may ultimately be regarded as exceptions within a series of comparatively low-value M&As.

Takeovers are not being confined to commodity-oriented companies wanting a much bigger presence in specialties. Producers with sales that predominantly come from added-value chemicals are also striving to strengthen their specialty operations in order to make themselves more effective rivals in a marketplace where competition will become even fiercer.

Evonik Industries, the Germany-based chemical, energy and real estate conglomerate, a large proportion of the €16bn 2008 sales of which came from specialties, disclosed late last year that it was planning to sell off its nonchemical activities to become an even stronger worldwide operator in specialties.

Klaus Engel, Evonik's chairman, told the German media that the company aimed to expand in specialties through acquisitions, although he ruled out a rumored takeover bid for LANXESS, one of its major German competitors.

Belgian chemical and pharmaceutical group Solvay has made it clear that it will be using much of the estimated €4.5bn earned from its sale of its pharmaceuticals business to US pharma firm Abbott Laboratories to reinforce its functions in specialty chemicals and added-value polymers.

However, there are doubts about the speed with which companies can either switch to specialties or bolster their existing positions in the sector. Consequently, many of the acquisitions could be slow to materialize and only take place over an extended period.

"A major problem - particularly in the existing economic conditions - is that companies are not able to quickly dispose of commodity businesses," says Alexander Keller, a partner at the energy and chemical competence center of the global Roland Berger Strategy Consultants, in Dusseldorf, Germany. "In addition, there are not many good specialty businesses whose owners would want to sell them - certainly not for big deals. Companies want to stay in specialties rather than get out of them."

The Netherlands-based company DSM, already a major global player in specialties, wants to sell its commodity activities in fertilizers, melamine and elastomers in order to expand its core activities in life sciences and performance materials.

"We have said that we want to finalize the sales of these businesses this year," says Nico Gerardu, DSM's management board member responsible for performance materials. "The disposal of them has been a bit slower than originally anticipated, which is not surprising, given the current conditions in the market. This will not affect our current investment plans, but bigger acquisitions over €1bn will not be done before the finalization of these divestments."

CAUTIOUS APPROACHIn addition to delays stemming from lack of funds, companies will also be holding back on acquisition decisions until they have a clearer picture of what and where the growth opportunities will be in the post-recovery global economy.

"The way certain industries recover - such as automobiles and construction - will determine what sort of changes in strategy are made by chemical companies supplying these industries," says Saverio Fato, global chemical industry sector leader at global management consultancy PricewaterhouseCoopers.

When talking about areas for expansion, companies say they have pinpointed the likely major social and economic requirements for the next decade - such as energy efficiency and lower carbon dioxide emissions, food and nutrition, health and clean water. But often, they have not yet selected the key technologies to which they need access.

Geographically, they all tend to stress the necessity of having a strong presence in emerging economies, particularly China and

"Once customers do not need application support for a chemical, it loses its premium and starts to become a commodity"

Alexander Keller, partner, energy and chemicals competence centre, Roland Berger Strategy ConsultantsIndia. But the difficulty with these markets is that they may entail the use of a different business model from that employed by specialty chemical companies in Europe, North America and Japan.

Currently, the big attraction of specialty chemicals in developed markets is the premium prices that can be gained from product innovation and customer services, particularly in the technical backup provided to ensure efficient application of the chemicals.

"Once customers do not need application support for a chemical, it loses its premium and starts to become a commodity," explains Keller. "This has happened, for example, to a part of the paper chemicals portfolio, additionally driven by the fact that these are large customers in a highly consolidated industry."

Specialty chemical companies such as DSM use their close contacts with customers through their services network to detect ideas for innovations that will meet their customers' needs. Often, they jointly develop new products with their customers.

SPECIALTY INNOVATIONDSM has an open innovation policy to bring new technologies into the company from universities, research institutes and startups to develop them into new business platforms.

"We depend on customers for short-term innovations and on our open innovation system, combined with our own ideas, for longer-term development of new technologies," says Rob van Leen, DSM's chief innovation officer.

In emerging markets, however, customers do not place so much value on innovation and technical support as their developed-world counterparts. As a result, they are not so willing to pay a premium price for specialties.

"In markets like China, specialty chemicals are more price-driven and a significant share of customers are less educated in the use of high-end chemicals used in products in Europe and North America," says Keller.

"The European and US specialty companies will continue to hold on to the high-end sectors in these markets. The fastest-growing and most competitive parts of these markets will be in the low and middle range of chemicals, which will be more price sensitive with less demand for application support."

Over the next decade European, North American and Japanese specialty chemical companies wanting to be active internationally will have to be able to compete in the price-oriented emerging markets.

They will also have to be well placed in the markets of the developed world, which will still account for the majority of specialty chemical sales. That means investing money and resources into R&D operations and service networks manned by people with a lot of skill and know-how.

"Chemical companies are now having to give a lot of importance to gaining and retaining talent," says Fato. "The search for talent for innovation activities and front-line services will be a major driver behind acquisitions in specialties."

Not only companies but regions with chemical clusters, particularly in Europe, are trying to reinvent themselves so that with the help of local skills and expertise, especially in academia, they can become more reliant on specialties.

In Teesside, northeast England, where the main Wilton chemical complex has, in recent years, lost around one-third of its capacity in commodity chemicals, local specialty and fine chemical companies are collaborating to market each other's technologies around the world.

"We have such a rich vein of fine and specialty chemical companies, plus emerging bio-specialty companies, in the northeast of England," says Stan Higgins, CEO of the North East Process Industry Cluster (NEPIC) representing 500 companies, which is helping organize the collaborative effort.

In their drive to revitalize their activities in specialities, clusters in Europe have the benefit of decades of chemical production, a lot of it in added-value products. Many chemical companies do not have that advantage.

"A specialties business cannot be developed at short notice," warns Gerardu. "If you want to be successful in specialties, you have to have an infrastructure of people in innovation and services, and that cannot be built overnight. It is something that can take years to do."

lunes, 15 de febrero de 2010

NEWS IN THE CHEMICAL INDUSTRY

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

Vistas de página en total

GREEN CHEMICALS

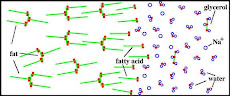

The Green Seal certification is granted by the organization with that name and has a great number of members contributing with the requirements to pass a raw material or a chemical product as "green". Generally for a material to be green, has to comply with a series of characteristics like: near neutral pH, low volatility, non combustible, non toxic to aquatic life, be biodegradable as measured by oxygen demand in accordance with the OECD definition.

Also the materials have to meet with toxicity and health requirements regarding inhalation, dermal and eye contact. There is also a specific list of materials that are prohibited or restricted from formulations, like ozone-depleting compounds and alkylphenol ethoxylates amongst others. Please go to http://www.greenseal.com/ for complete information on their requirements.

For information on current issues regarding green chemicals, see the blog from the Journalist Doris De Guzman, in the ICIS at: http://www.icis.com/blogs/green-chemicals/.

Certification is an important — and confusing — aspect of green cleaning. Third-party certification is available for products that meet standards set by Green Seal, EcoLogo, Energy Star, the Carpet & Rug Institute and others.

Manufacturers can also hire independent labs to determine whether a product is environmentally preferable and then place the manufacturer’s own eco-logo on the product; this is called self-certification. Finally, some manufacturers label a product with words like “sustainable,” “green,” or “earth friendly” without any third-party verification.

“The fact that there is not a single authoritative standard to go by adds to the confusion,” says Steven L. Mack M.Ed., director of buildings and grounds service for Ohio University, Athens, Ohio.

In www.happi.com of June 2008 edition, there is a report of Natural formulating markets that also emphasises the fact that registration of "green formulas" is very confused at present, due to lack of direction and unification of criteria and that some governmental instittion (in my opinion the EPA) should take part in this very important issue.

Also the materials have to meet with toxicity and health requirements regarding inhalation, dermal and eye contact. There is also a specific list of materials that are prohibited or restricted from formulations, like ozone-depleting compounds and alkylphenol ethoxylates amongst others. Please go to http://www.greenseal.com/ for complete information on their requirements.

For information on current issues regarding green chemicals, see the blog from the Journalist Doris De Guzman, in the ICIS at: http://www.icis.com/blogs/green-chemicals/.

Certification is an important — and confusing — aspect of green cleaning. Third-party certification is available for products that meet standards set by Green Seal, EcoLogo, Energy Star, the Carpet & Rug Institute and others.

Manufacturers can also hire independent labs to determine whether a product is environmentally preferable and then place the manufacturer’s own eco-logo on the product; this is called self-certification. Finally, some manufacturers label a product with words like “sustainable,” “green,” or “earth friendly” without any third-party verification.

“The fact that there is not a single authoritative standard to go by adds to the confusion,” says Steven L. Mack M.Ed., director of buildings and grounds service for Ohio University, Athens, Ohio.

In www.happi.com of June 2008 edition, there is a report of Natural formulating markets that also emphasises the fact that registration of "green formulas" is very confused at present, due to lack of direction and unification of criteria and that some governmental instittion (in my opinion the EPA) should take part in this very important issue.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario