Developing a

feedwater chemistry program that will minimize corrosion across a variety of

metallurgies doesn’t have to be difficult. This article reviews the

requirements for three common metallurgies in condensate and feedwater piping

and the chemistry options that operators have to minimize corrosion in this

critical area of the plant.

Alloys found in

the condensate and feedwater systems of power plants include carbon steel for

piping, pumps, and in some cases heat exchangers. Many systems still have some

copper-based alloys from admiralty brass, and copper-nickel (Cu-Ni) alloys all

the way to 400 Series Monel, primarily as feedwater heater tubes.

The major

corrosion mechanisms affect the carbon steel and copper alloys. These include

flow accelerated corrosion (FAC) and corrosion fatigue in carbon steel as well

as ammonia-induced stress corrosion cracking, and ammonia grooving in copper

alloys. FAC can have a variety of appearances (Figures 1 and 2).

1 Typical. Classic flow-accelerated

corrosion (FAC) orange peel texture with no oxide coating. Courtesy:

M&M Engineering Associates Inc.

|

2. Atypical. Compare the previous example

with this one showing an unusual pattern of FAC in a deaerator. Courtesy:

M&M Engineering Associates Inc.

|

Gradually, as

aging feedwater heaters are replaced, plants often choose to go with a

stainless steel alloy such as 304 or 316 for feedwater tubing. When the last

copper feedwater heater is replaced, a change in feedwater chemistry is in

order.

Stainless Steel

Stainless steel

is protected by a tight adherent chromium oxide layer that forms on the

surface. Stainless steels alloys are resistant to essentially all the corrosion

mechanisms that commonly affect copper and carbon steel alloys in feedwater.

There is the

tendency to think that stainless steel is the perfect alloy to replace

copper-alloy feedwater heaters. However, stainless steel has its own Achilles

heel: Chlorides can cause pitting, and chloride and caustic have, in some

cases, led to stress corrosion cracking (SCC).

Typically,

these chemicals are not present in sufficient concentration to cause corrosion

on the tube side of feedwater heaters. However, there are cases where

contamination of the steam that feeds the shell side of the stainless

steel–tubed heat exchanger has resulted in SCC.

Remember, it is

not the average concentration of the chloride or caustic that is of concern.

Spikes in contamination can collect and concentrate in the desuperheating zone

of the shell side of the feedwater heater and in crevices. These are the areas

that can fail, even if the steam is pure most of the time. Where there is a

potential for chloride or caustic contamination of the steam, stainless steels

may not be the best fit or, at a minimum, alloys should be considered that have

a higher resistance to chloride attack, such as 316 or 904L. In general

however, it may be more productive to work on eliminating the potential for

contamination than to alloy around the problem.

The most

commonly quoted downside to the replacement of copper-alloy feedwater heater

tubes with stainless steel is the difference in thermal conductivity. A quick

look at the reference values will show that a 304 stainless steel has only

one-seventh the thermal conductivity of admiralty brass and about one-third the

conductivity of 90-10 Cu-Ni alloy. Numerous papers have been published

discussing why these “textbook” values are unlikely to be experienced in the

real world. This is certainly an important consideration with condenser tubes,

where the potential for cooling water–side deposits and condenser cleanliness

is likely to have a much more prominent effect on heat transfer than the

textbook thermal conductivity of the tube metal. However, feedwater heater

tubes should have little steam- or water-side fouling. Other factors, such as

tube thickness may offset some of the thermal conductivity loss, and there are

other design factors, such as susceptibility to vibration damage, to consider

in selecting a material.

Carbon Steel

Carbon steel is

passivated by the formation of a dual layer of magnetite (Fe3O4). The layer

closest to the metal is dense but very thin, whereas the layer closest to the

water is more porous and less stable. Hydroxide ions are necessary for the

formation of magnetite. Due to the common utility practice of using feedwater

to control the final temperature of superheat and reheat steam, the source of

hydroxide in feedwater must be volatile, and ammonia or an amine is generally

used for this purpose. A solid alkali such as sodium hydroxide must never be

introduced ahead of where the takeoff to the attemporation is located.

Ammonia is very

volatile, remaining in gaseous state during initial condensation. This may

occur in the deaerator, condenser, or on the shell side of a feedwater heater.

This lowers the effective pH of the first condensate and increases the

solubility of the magnetite layer in that area. This can increase the rate of

FAC in these areas.

For carbon

steel, higher pH values are better for the production and stability of

magnetite. Operating with low pH values in the feedwater and condensate

destabilizes magnetite and increases the rate of FAC on carbon steel in the

feedwater system. It also increases the iron in the feedwater, which generally

winds up on the waterwall tubes. This iron deposition increases the risk of

under-deposit corrosion mechanisms, inhibits heat transfer across the tube, and

increases the frequency of chemical cleaning.

A case can be

made for the use of carbon steel feedwater heater tubes, particularly alloys

such as T-22, which contains 2.25% chromium (Cr) and 1% molybdenum (Mo). It has

better thermal conductivity than stainless steel, is highly resistant to

chloride SCC, and because it contains 2.25% Cr, is generally considered immune

to FAC.

Copper Alloys

Copper alloy

corrosion in the power industry has been studied in depth due to problems with

copper deposits on the high-pressure (HP) turbine that reduced turbine

efficiency and the maximum load that the unit could produce.

Zinc-containing

brass alloys such as admiralty brass are particularly susceptible to attack

from ammonia vapors. This can result in ammonia-induced SCC on the steam side

of the condenser or feedwater heater. The same alloys are susceptible to a

mechanism termed “ammonia grooving,” where steam and ammonia condense on the

tube sheet and support plates of the feedwater heater and run over the tubes,

creating a narrow group of corrosion directly adjacent to the tube sheet or

support plate. Copper alloys containing nickel are far less susceptible to

ammonia-induced SCC.

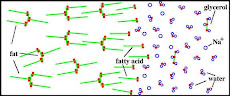

Admiralty brass

alloys have the additional concern of corrosion of zinc in the alloy due to

low-pH conditions in the feedwater or steam. Over time, the zinc can leach from

the brass matrix, leaving only the copper sponge, which has little structural

strength. This mechanism is called dezincification. Although not as common,

copper-nickel alloys can also suffer from dealloying (Figure 3).

3. Weakened. Dealloying, dezincification in

brass alloys, or removal of nickel from copper-nickel alloys will destroy the

strength of the material. Courtesy: M&M Engineering Associates Inc.

|

There are three

separate rates associated with the rate of corrosion of any copper alloy. These

have been referred to as:

·

Rd—the rate at which corrosion products leave the surface as a

dissolved species in the water (typically copper ammonium complexes).

·

Rf—the rate at which corrosion products (copper oxides in

operating steam and condensate systems) form on the surface of the metal.

·

Rs—the rate at which copper corrosion products (typically

oxides) leave the surface as suspended particles.

These rates are

not necessarily correlated with each other and may not occur under the same

chemical conditions. Copper oxide formation (Rf) can be protective, minimizing

further corrosion of the alloy—as long as it remains intact. When chemical

conditions change, such as moving from an oxidizing to a reducing condition, Rd

and Rs may increase dramatically. Protective copper oxides are aggressively

dissolved by the combination of ammonia, carbon dioxide, and oxygen. The most

common place for all three of these to be present is in a copper-tubed

condenser that has air in-leakage issues.

Once these

corrosion products are dissolved or entrained, they are subject to downstream

chemical conditions, where a change in the at-temperature pH or the oxidation

reduction potential (ORP) in a specific location can cause the copper to “plate

out” as copper metal on suction strainers, pump impellers, or on another

feedwater heater tube surface in the form of a pure copper “snakeskin.” They

may also continue on through the feedwater system and deposit on a boiler or

superheater tube or on the HP turbine. Similar conditions (plating out) can

occur in stainless steel sample lines, making the accurate measurement of

copper corrosion products in a conventional sample line difficult.

Chemical

Control of Feedwater

Proper alloy

selection, either in the initial construction or as equipment is replaced,

should be carefully considered. Once the decision is made, the water chemistry

program must follow to minimize corrosion of the feedwater equipment and

deposits in the boiler and turbine. The more metals there are in the mix, the

more things need to be considered in the chemistry program. Copper alloys, in

particular, force compromises, as the optimum chemistry requirements for copper

and iron cannot be met simultaneously.

Feedwater pH

Control. The pH limits recommended on all ferrous-alloy condensate and

feedwater piping are now a minimum of 9.2 with an upper limit of 9.8 or even

10.0 in systems with an air-cooled condenser. If there are no copper alloys in

the system, the biggest downside to having too much ammonia in the system is

the frequent replacement of cation conductivity columns rather than corrosion

in the carbon steel.

For those

operating heat-recovery steam generators (HRSGs), there can be a significant

drop in pH of the low-pressure (LP) drum water as ammonia (and some amines)

leaves with the LP steam. It is important that the LP drum pH be monitored

continuously and controlled certainly within the range of 9.2–9.8. Some suggest

a minimum pH of 9.4 for water in the LP drum to protect downstream

high-pressure and intermediate-pressure economizers.

The current

recommended pH range for systems that have copper in either the main condenser

or feedwater heaters is 9.0–9.3. (See the sidebar for an explanation of the

necessity of accurate pH measurement.) Laboratory studies have shown that is

actually the minimum range for avoiding copper corrosion in the copper alloys

used in feedwater heaters and condensers. Lower feedwater and condensate pH

values (for example, pH 7.0) have higher copper corrosion rates than pH 9, particularly

under oxidizing conditions.

Measuring pHAccurate pH measurement in

high-purity water is difficult. The very low specific conductivity of the

water combined with the potential for ammonia to be lost and carbon dioxide

to be simultaneously absorbed by the sample while it is being collected and

measured can lead to confusing results. Inaccurate pH monitoring can result

in over- or under-feeding of ammonia or amines.

Continuous online pH monitoring

using pH probes specifically developed for high-purity water can improve the

accuracy and reliability of the measurement.

The pH of high-purity waters

can also be calculated from a combination of the specific conductivity and

cation conductivity results. This can be done manually, or there are

commercially available instruments that display a calculated and measured pH.

Due to these issues with pH,

specific conductivity is often used to control the ammonia feed instead of

controlling directly from a pH meter.

|

Ammonia or

Amines. The addition of ammonia to condensate is the simplest and most

direct way to raise the pH of the condensate and feedwater into the desired

range to create and stabilize the magnetite layer. In all-ferrous systems,

there should be a clear case or desired objective for using any other chemical

for pH control. On the other hand, the use of neutralizing amines in the

utility steam cycle has a long, successful history, particularly in units that

have copper alloys in the feedwater heaters.

The decision to

use neutralizing amine for iron corrosion should be based primarily on the need

to provide more alkalinity (a higher pH) in an area of concern than can be

achieved simply by increasing the ammonia levels. This may include areas where

steam is first condensing into water, such as in an air-cooled condenser, or

where water/steam mixtures are being released, such as in the deaerator.

Although amines

are more common when copper alloys are found in the feedwater system or

condenser, their presence does not necessarily require the use of a

neutralizing amine. There are many mixed-metallurgy units that operate using

ammonia and that carefully control air in-leakage with very low copper

corrosion rates.

The choice of

which neutralizing amine to use (and there are many) should be based on where

and how it is to function. It is critical that both the basicity (amount of pH

rise per ppm of amine) and volatility of the amine (the ratio of what goes into

the steam versus what remains in the water) is matched to the application.

The criticism

of the general use of amines in high-pressure utility cycles is centered on two

issues: the degradation of these organic molecules in the steam cycle

(particularly in the superheater and reheater) and the consequence of these

degradation products—namely, an increase in the cation conductivity of the

condensate and feedwater.

It has been

long known that as neutralizing amines pass through the steam cycle, they break

down into ammonia and organic acid byproducts such as acetic acid, formic acid,

and carbon dioxide. The percentage of degradation is certainly specific to the

particular amine and concentration in the steam, but it is also unit specific

and depends, at a minimum, on the size and complexity of the superheater and

reheater piping, where it appears most of the degradation occurs.

Those who

advocate for the sole use of ammonia instead of amines point to the degradation

of these products and see them as “single-use” chemicals—good for only one trip

around the steam cycle. If all the amine degrades with one trip through the

superheater and reheater, it cannot be available to minimize the corrosion of

copper condenser tubes or affect the pH of a steam/water mixture in the

feedwater, and so it would not be worth the trouble.

However, there

are many different factors that affect amine degradation rates and, therefore,

how beneficial an amine might be in the system. These include the operating

pressure of the unit, where the copper alloys are located, and whether the unit

even has a reheater. For example, in the standard triple-drum HRSG, a

significant percentage of the amine may leave with the LP steam, where it recycles

through the condenser and preheater sections of the HRSG and never sees the

high-temperature areas. This would significantly increase its longevity and

usefulness.

All these

factors need be taken into account when considering whether an amine would be beneficial

at a particular plant. It would behoove anyone who is considering trying an

amine to set up to sample and test for the amine and degradation products

around the cycle and also quantify improvements to iron and copper corrosion

rates. That will help them determine, for their particular unit, if the

benefits of amine use outweigh the costs.

The degradation

products of any amine will add to the cation conductivity of the condensate and

feedwater. The longevity and chemical structure of the amine will affect the

cation conductivity “bump” that the plant will experience. Degassed cation

conductivity can remove carbon dioxide but generally not all the other organic

acids produced by amines. So if amines are used, the normal cation conductivity

will need to be adjusted for the presence of these products.

Controlling

Oxidation Reduction Potential

It can be

generalized that the ability of an alloy to withstand corrosion is a function

of the stability and tenacity of the oxide layer that forms on the metal surface.

As discussed above, stainless steel has a very tight and tenacious layer of

chromium oxide that prevents corrosion of the metal from oxygen and from the

common pH ranges found in feedwater.

Establishing

and maintaining a good oxide layer on carbon steel is critical to minimizing

FAC. Copper oxides are also protective—as long as they remain in place.

Particularly in

the case of copper alloys, the oxide layer can be easily disrupted. Research

has shown that one of the most corrosive times for copper alloys is when they

cycle between a reducing and oxidizing condition. Therefore, it is imperative

that mixed-metallurgy feedwater systems contain sufficient reducing agent such

as hydrazine or carbohydrazide to maintain a reducing condition at all times.

A reducing

condition is not the same as the absence of dissolved oxygen. Regardless of how

well the deaerator is functioning, if there are copper feedwater heaters in the

system, the continuous addition of a reducing agent is required to achieve the

negative ORP that is protective of copper alloys.

All volatile

reducing agents used in utility cycles break down at temperatures typically

associated with HP feedwater heaters or the economizer—and certainly by the

time the water reaches the boiler. Therefore, regardless of which reducing

agent is added to the condensate pump discharge, there is no protection for the

copper alloy condenser tubes against the combined effect of dissolved oxygen,

carbon dioxide, and ammonia. This is why it is so critical to minimize air

in-leakage and control feedwater pH.

Many units have

been replacing copper alloy feedwater heaters with carbon steel or stainless

steel tubes over the years. When the last copper feedwater heater is replaced,

the reducing agent can almost always be eliminated, regardless of whether the

condenser contains copper alloys or not.

Carbon steel

corrosion is inhibited by the presence of small amounts of dissolved oxygen.

Research has shown that as little as 5 ppb to 10 ppb of dissolved oxygen

significantly reduces the rate of FAC under feedwater conditions. This occurs

because the dissolved oxygen present in the low-temperature feedwater (from the

condenser to the deaerator) forms iron oxides that fill in the pores of the

outer layer of the magnetite, dramatically improving its stability. Even in the

absence of any measurable dissolved oxygen, after the deaerator, the ORP

remains positive and increases the stability of the magnetite layer through the

HP feedwater heaters and economizer.

The formation

of these more resilient protective oxides is the basis of oxygenated treatment,

which is successfully used on all supercritical plants in North America and

many HP drum units. However, simply discontinuing the use of a reducing agent

should never be confused with oxygenated treatment, where pure oxygen is purposefully

injected, the deaerator vents are closed, and the dissolved oxygen levels in

the feedwater are an order of magnitude higher than in a conventional feedwater

system.

Stable

feedwater chemistry in the absence of a reducing agent continues to strengthen

the passive oxide layer throughout the feedwater piping over time. Therefore,

although dissolved oxygen levels may temporarily spike during a startup, it is

also unnecessary to add a reducing agent during layup or for the subsequent

startup. ■

— David

Daniels is a POWER contributing editor and senior principal scientist

at M&M Engineering Associates Inc.